On November 29, North Korea launched a missile from Pyongsong, South Pyongan Province. After flying to an altitude of 2,800 miles, the missile splashed down in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (CNN; USA Today). The test broke a hiatus that lasted over two months, escalating tensions on the peninsula in the months leading up to the Olympic Games in South Korea. Not only was the test a break in the brief respite in testing, it marked a massive improvement in North Korea’s arsenal. Several key questions arise from the test. 1) What capabilities does the new missile add to North Korea’s program? And should we be scared of those new abilities? 2) How does the test alter the way we respond to North Korean provocations? 3) Are we inching closer and closer to a war on the peninsula?

How Does the New Missile Enhance Pyongyang’s Abilities?

The missile tested on November 29 was a Hwangsong-15 type Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, the largest and longest reaching missile in North Korea’s arsenal. David Wright, co-director of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, estimated that the missile, flown on a more standard trajectory, has an estimated range of 13,000km (8,100 miles)[Union of Concerned Scientists]. Analysts have cautioned, however, that the missile was most likely tested with a reduced payload to exaggerate its overall capabilities. Some estimates place the range of the operational missile, carrying a 500kg payload, to be around 8,300km (38 North).

Despite its range, some other key aspects of the missile differentiate it from the rest of North Korea’s arsenal. Compared to the Hwangsong-14, the ICBM North Korea tested in July, the Hwasong-15 is bigger, has more engines, and features a guidance system which is simpler and more effective than previous variations on other North Korean missiles (38North). Another key aspect of the missile is the Hwasong-15’s BMD defenses. The Hwasong-15 has the capability to carry a wide variety of simple decoys, pieces used to fool interceptors into hitting the wrong target. Several experts agree that the current state of American Ballistic Missile Defense, the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense System or GMD, is not capable enough to be relied on in the event that an operational Hwasong-15 is launched against the country (The National Interest). Technologically, the missile not only is a step up for Pyongyang, it showcases that North Korea has mastered a wide variety of technological aspects for their ICBM program, providing them with a stronger ability to strike the United States mainland and get through the web of American missile defense. It’s a scary leap forward indeed.

The Hwasong-15 is the technological leap forward the international community has been fearing for some time. Not only does the missile appear more accurate and reliable than other North Korean missiles, it also has the theoretical ability to carry a nuclear warhead to the United States mainland, even if the operational length of the missile is shorter than test analysis shows. North Korea may now turn its focus to improving the Hwasong-15 as well as shrinking its nuclear weapons to fulfill its penultimate goal: having the ability to strike the United States mainland with a reliable nuclear-tipped ICBM.

Running out of Options: How Do We Respond in the Age of the ICBM?

International reactions to Pyongyang’s test were strong, yet not strong enough to provoke. Marked with shows of strength and tough diplomacy, reactions have centered on one goal: showcasing strong forces and alliances as a method of deterrence. However strong they were, the responses also needed an element of tempered diplomatic maneuvering to avoid exacerbating the situation.

While moving through the typical South Korean bureaucratic channels–Moon Jae-in called an emergency meeting of the National Security Council as the military worked to assess and respond to the test–Seoul launched a precision strike missile within 6 minutes of the North Korean test. Seoul’s response is striking for many reasons. South Korea had some intelligence pointing to a possible launch; it involved cooperation between the Army, Air Force, and Navy; and it “offer[ed] potent operational evidence of parts of its Kill Chain preemptive strike system and Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) plan,” two parts of South Korea’s defense strategy (The Diplomat). Moon Jae-in also worked the diplomatic reams of the crisis. In a phone call with President Trump, the two agreed to discuss further measures to punish North Korea for the test (Reuters).

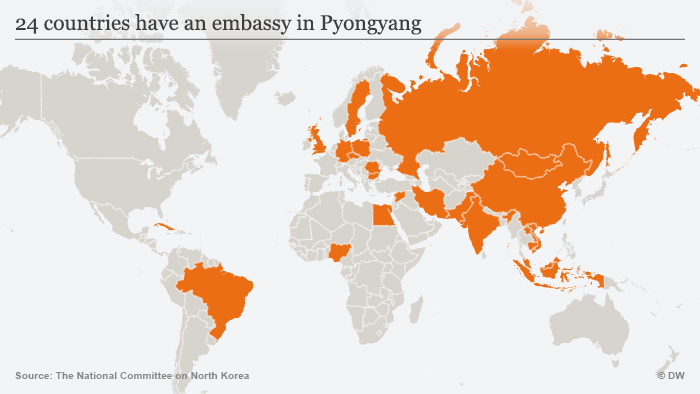

While South Korea’s response was one of measured strength and cooperative diplomacy, the United States took a more hawkish stance. American Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley, at an emergency meeting of the Security Council, called on nations to isolate Pyongyang by cutting all ties with North Korea, while also arguing that the test brings the peninsula closer to war (TIME). Currently, 24 nations have relations with North Korea and there are 47 North Korean diplomatic missions scattered throughout the world (CNN). However, many nations have expelled North Korean diplomats for a slew of reasons. Following its September nuclear test, 6 nations–Spain, Kuwait, Peru, Mexico, Egypt, and the Philippines–sent North Korean diplomats packing while Uganda cut all military ties in May of 2016 (Reuters). Malaysia also expelled its North Korean Ambassador following the assassination of Kim Jung-nam earlier this year (The Guardian). As North Korea continues to push for more advanced weapons and eliminates perceived threats to Kim Jung-un by any means, more nations may choose to cut ties with North Korea, though some will likely stay to act as mitigators between North Korea and the outside world.

(Image Source: The DW)

(Image Source: The DW)

President Trump, who has been a vocal critic of Kim Jung-un since ascending to the White House, has also lashed his teeth following the test. On Twitter, Trump said “the situation will be handled,” and called for tougher sanctions on the regime (Twitter). Outside of calling for political actions, Trump has lashed out at Pyongyang’s leader, calling Kim Jung-un a slew of names including “Little Rocket Man” (Twitter), and “Sick Puppy” (Politico). Even before his presidency, Trump has been very vocal, and often times bellicose, in criticising the North Korean regime (CNN). Despite the vitriolic rhetoric by Trump, he has hinted at the possibility of meeting with Kim Jung-un, but has said the meeting would have to happen under the right circumstances (BBC).

China, North Korea’s greatest ally in the world, demurred the test, expressing “grave concern and opposition” (CNBC). Despite having strong reservations about the nuclear and missile program, China still stands by North Korea. As American and South Korean forces conducted annual drills, China’s Air Force flew on routes and in areas it has never flown over the East and Yellow Seas, a warning to Trump against provoking Pyongyang (Forbes). The drills highlight a grave possibility if hostilities resume: China may come to the aid of North Korea. As if the possibility of Chinese intervention in a resumed Korean conflict weren’t enough to raise hairs, a Chinese provincial newspaper ran a full-page advisory giving advice to citizens called “General Knowledge about Nuclear Weapons and Protection.” The advisory ran cartoons about how to act in a nuclear attack, eventually forcing the paper to calm citizens worries (Washington Post).

Global reaction to the test was measured not in its strength or creativity in calls to action. Rather, the reactions and policy proposals following Pyongyang’s test showcased just how divided the world is on the issue. Conflicting issues will continue to mire any chance of success in bringing North Korea to the discussion table.

The North Korean security issue is a complex one, requiring a combination of hard-line isolation and more tactful diplomacy to resolve. However, there seems to be no clear path forward; diplomatic actions are likely to be cheated by Pyongyang and more aggressive actions will exacerbate tensions. The most effective actions, however, are the ones taken in unison. Nations who have a major stake in the situation–America, Russia, China, South Korea, and Japan to name a few–need to unify in a detailed approach leveling carrots and sticks toward Pyongyang. Without a clear, unified path forward, North Korea will continue to test as a way to split world powers and maintain a system of global order which favors continuing nuclear and ballistic missile tests as a way for North Korea to survive and get what it desires.

Are we Inching Closer to the Edge?: The Possibility of War on the Peninsula

Following every new advancement in Pyongyang’s capabilities, the world ponders the effects of resumed conflict on the peninsula, and following this test was no different. Barry Posen, an MIT political science professor, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times speculating the potential costs of a war on the Korean Peninsula (New York Times). American Senator Tammy Duckworth commented that the majority of the American public doesn’t know exactly how close to war the situation really is (Vox).

North Korea, for its part, has not been working to squash such fears. After a rhetorical tit-for-tat, a North Korean spokesman was quoted as saying that “these confrontational warmongering remarks cannot be interpreted in any other way but as a warning to us to be prepared for a war on the Korean Peninsula,” (Newsweek). An article in the Korean Central News Agency strongly demurred the recent actions by the Americans, calling the outbreak of war “an established fact” (KCNA).[1] Such comments have done nothing but strengthened the idea that war is inevitable, but is it really?

Despite the highly tense rhetoric, war is still far from an established fact. Barry Posden, in The New York Times, writes that “the complexity, risks and costs of a military strike against North Korea are too high.” He reaches this conclusion by citing that America would have to make several unobvious maneuvers, a task with a high chance of failure. Also, North Korea would, despite the success of a preemptive attack, have a chance to respond, and “the detonation of even a small number of nuclear weapons in North Korea would produce hellish results” (New York Times).

Another key reason war is further from resumption is the rationality behind North Korea’s continued pursuit of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles (Wall Street Journal). Kim Jung-un views the program as a way to ensure his security as a global leader and understands that war would most likely lead to his unseating. Those around him, though they are unable to rein in Kim, also face a scenario of loss of power if hostilities resume.[2]

As the situation stands today, we are no closer to war than we were a few days or months ago. The most realistic chance of war comes from the high likelihood of a miscalculation by either Trump or Kim in either rhetoric or action. Maintenance of the status-quo along with tough sanctions and pressure, though a flawed and possibly resultless strategy, continues to be the best of the worst case on the peninsula. It is only through a mix of pressure and creative diplomacy, backed by the entire international community, presents the greatest opportunity to bring Pyongyang to the negotiating table, though it still does not guarantee that negotiation will lead Pyongyang to a freeze.

Notes:

[1] Source is from North Korean state media and therefore will not be linked to in this post. However, the cited Newsweek, article offers a good analysis of North Korea’s recent rhetoric, including the KCNA article.

[2] David Rothkopf, a senior fellow at SIAS, offers more insight into why a war on the peninsula is not as close as the media makes it seem. His basic framework is similar to the one I attempted to create, though his wonderful piece in the Chicago Tribune hones in on the possibilities on the Korean peninsula in more focused and detail tone than my own. I highly recommend his piece: David Rothkopf, “Here’s how the North Korea nuclear standoff will end,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 2017. (This is today’s Daily Reading.)

Corrections:

12/8: A previous version of this article said that the precision test was performed after Moon Jae-in called a meeting of the National Security Council, when in fact the two happened fairly close to each other.